Extract:

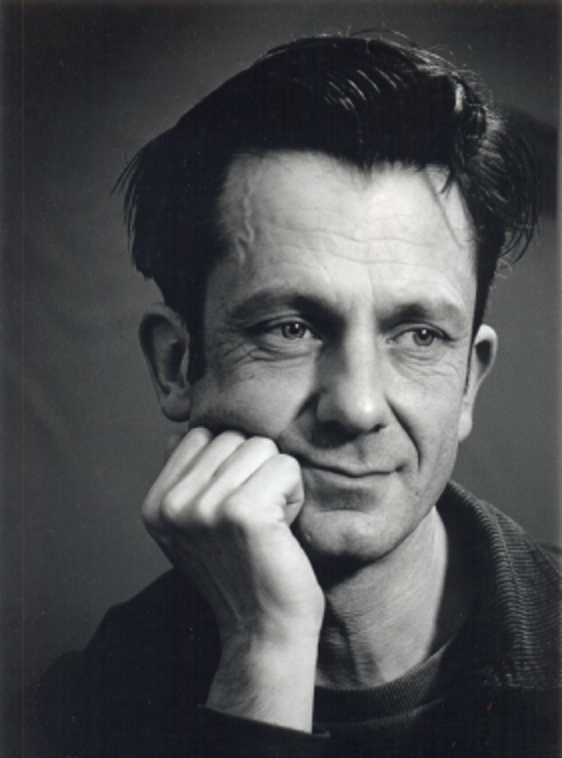

Craven had been a shade worried that he might have difficulty recognizing the party leaders, but need not have worried. A giant of a man, grossly overweight and dressed in what approximated to the uniform of a Group Captain but including several flamboyant and presumably unlawful additions of his own, burst out of a first-class compartment followed by half a dozen respectful henchmen soberly dressed in overcoats and mackintoshes. Craven put him in his mid-fifties, but later learned that he was forty-six.

Oakman performed the introductions, to which the deputy leader responded with studied lack of courtesy, as if deciding which of those before him were worth acknowledging. Craven alone seemed to pass muster.

‘Pleased to meet you,’ said Craven, adding ‘sir,’ in deference to the man’s rank. He half expected Goring to insist upon a less formal style of address, but this did not occur. His unfavourable impression of the Deputy Leader was confirmed. Though to be fair, he told himself, the man had had a distinguished war record, some time ago though it now was.

At the introduction of Christine Goring’s interest revived, he looking her up and down with approval as they shook hands. The Deputy Leader’s sexual appetite was notorious. ‘Charmed.’

Oakman concluded, ‘And Mr Basil Holmes, Deputy Chief Constable.’

Goring responded with a curt nod. ‘The rally starts at ten-thirty, I understand.’

‘Yes, sir. I’ll take you to the Market Square.’

Although the square was less than half a mile distant, the journey required the assistance of half a dozen taxis which Oakman had arranged to stand by. Goring’s bulk was such that he practically filled the back of one of them, there being room otherwise only for one of his aides. Craven found himself sharing with Oakman, Barrington, and another of the deputy’s minions. There was already a substantial crowd making their way to the town centre, whether as participants, spectators, or simply early Christmas shoppers it was difficult to tell, save for those who carried banners. One group recognized Goring and gave a thin cheer, which he acknowledged by flapping a hand disdainfully.

‘I need to mention something, Craven,’ said Oakman crisply, albeit sotto voce, ‘and now seems as good a time as any.’

‘Go ahead.’

‘I – er – hear that you and your wife no longer live together.’

‘I’m afraid that’s right.’

‘The NatSo party, as you know, places great stress on family values.’

‘You mean I should attempt a reconciliation?’

‘That would be the ideal. Of course, I don’t know how feasible that may be.’

‘The main problem is that she’s not in sympathy with NatSo policy.’

‘Indeed. That’s unfortunate. Is there any possibility she might be persuaded to change her views?’

‘Most unlikely, I think. I’ve tried, of course.’

Oakman nodded soberly. ‘Is there anything else?’ asked Craven.

‘There are rumours – I put it no stronger – about the relationship between yourself and one of our junior party members. From what I know of the young lady, she would be an ideal choice were you a single man, but of course you are not.’

‘She’s a very enthusiastic worker for the cause.’

‘So I gather. The point is of course that in order to be elected you need to appeal to the public in general, not just loyal party members. And I doubt whether the electorate would understand your position.’

‘What would you like me to do?’

‘I leave it to you. Remember however that discretion is all-important.’

In other words, take care not to be found out. ‘I’ll bear what you say in mind, of course. Be assured I shall not do anything which might reflect adversely upon the party.’

This was the sort of claptrap popular with officials of all parties throughout the ages. Oakman came as hear as he could to expressing approval, with a brisk nod and the words, ‘Good man.’

By now they were driving along the main street of Castletown, a thoroughfare ill-suited to a motorcade, or modern traffic conditions of any kind. With the road closed and a police escort the taxis nevertheless managed to crawl the quarter-mile from Lime Tree Corner to the Market Square at least as quickly as the average motorist on a weekday. The weather was chilly and overcast. Banners welcoming the distinguished guests mingled with a rather sad collection of unlit Christmas decorations, mostly stars, fir trees and Santas.

No building in the Market Square possessed a convenient balcony whence the Deputy Leader could watch the parade, the impressive facade of the Shire Hall framing an entrance hall which though tall enough for two storeys in fact contained but one, with much wasted space. The Guild Hall opposite was similarly unsuitable, with stained glass windows through which it was difficult to see, and impossible to be seen. A temporary dais had therefore been erected in front of the Shire Hall, from which the NatSo dignitaries were enabled to view the proceedings.

Being familiar with the apathy of most citizens of Castletown, Craven was surprised by the degree of activity within the square. Flag-bearing NatSo youth were helping to decorate the platform, whilst a squad of uniformed police kept a motley group of counter-demonstrators at a safe distance on the far corner by the Midland Bank. Mostly they held ill-written placards expressing hostility to the NatSos and their policies in terms varying from ‘Castletown Says Down With Fashism’ (sic) to ‘Bugger Off, Goring’ and ‘You Fat Swine.’

It was twenty past ten by the time Craven’s taxi arrived in the square. Another was already discharging its load of Goring and his aide, who helped his chief disembark with a deference bordering on servility. Most of the crowd seemed welcoming, clapping and waving paper Union Jacks, though they were soberly dressed and subdued compared with the sort of crowds Craven could remember from his dreams. In front of the Midland Bank there was an exchange of insults between the pro- and anti-NatSo factions which however seemed unlikely to develop into serious trouble.

The Shire Hall had been taken over for the morning, and it was there that the final arrangements were made before they marched out on to the dais promptly at half-past ten, to a predictably mixed reception. Goring naturally occupied the place of honour in the centre, with Craven on his right. To the deputy’s left stood a couple of fawning henchmen from Central Office, while half a dozen NatSo candidates from elsewhere in the West Midland region grouped themselves on either side. As regional co-ordinator Oakman also enjoyed a prominent place, whereas Barrington, Aston and Christine had to position themselves as best they could. Everyone wore rosettes in the NatSo design, the barred Z in blue against a background of white, fringed red.

The town band struck up the national anthem, to which the whole crowd listened respectfully, followed by the tune the NatSos had made their own: ‘Land of Hope and Glory.’

This provoked a livelier response, many of the crowd joining in the singing, whilst Goring at first waved, then made the gesture which had become famous as the NatSo salute, raising both arms from the elbow with palms forward. Meanwhile he turned from side to side so that all in the crowd should obtain the best possible view of him, whilst the expression on his rather bloated face attempted to combine firmness of purpose, nobility, appreciation of his reception, and patriotism, not unmixed with self-satisfaction. The otherwise impressive effect was marred by the fact that the band had to repeat ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ almost immediately so as to drown out the Communist faction, who were singing to the tune Cwm Rhondda:

‘Who the fu-hu-huck ...

Who the fu-hu-huck ...

Who the fuckin’ell are you?

Who the fu-hu-ki-hi-n’ell are you?’In the same situation the Liberal candidate, a university lecturer and lay preacher, would have been unlikely to recognize any words alternative to ‘Bread of Heaven,’ whilst those of the other main parties would have responded with icy disdain. Goring by contrast turned to the offenders, and with a malignant grimace treated them to a form of salute which long predated that of the NatSos, handicapped somewhat by his fingers being encased in woollen mittens against the cold. Unsurprisingly this drew a corresponding response from the offending section of the crowd, and the situation was not retrieved until the band-leader ordered his men to strike up ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ again.